Resource nationalism in Africa: issues for Chinese investors

1. SYNOPSIS

1.1 In this article, lawyers from Ashurst LLP and Guantao discuss the evidence of growing resource nationalism across Africa and how Chinese investors may take steps to mitigate their risk.

1.2 Ashurst LLP is a leading international law firm with 27 offices in 16 countries. Guantao is a leading law firm in China which has been recognised by the Ministry of Justice of China as a Ministerial-level Elite Law Firm. Ashurst and Guantao formed a strategic alliance in 2008 and have been co-operating closely since then.

2. Introduction

2.1 China has a long history of investment in Africa and, with over US$80 billion invested between 2005 and 2017, its relationship with the continent is an important one.

2.2 Much of the Chinese investment in Africa concerns energy and mineral resources with 40 per cent invested in metals and 33 per cent in energy. In recent months a number of African states have implemented tighter controls over their natural resources and foreign entities' access to them: so-called "resource nationalism".

2.3 This article considers how recent, and future, measures put in place may affect Chinese investors, what protections may be available and how disputes may be resolved through international arbitration.

3. Resource Nationalism in africa today

3.1 "Resource nationalism" is the phrase used to describe the tendency for states to take (or seek to take) direct and increasing control of economic activity in natural resource sectors. This is usually a protectionist policy designed to restrict the exploitation of a natural resource by investors from other countries. Resource nationalism is not a new phenomenon and can take many forms. Numerous examples can be found throughout history, encompassing the Middle East, Latin America and Asia.

3.2 However, recently there has been a notable increase in resource nationalism in Sub-Saharan Africa. Examples of this include:

(a) Increased royalty rates or taxes on companies operating in the mining industry

(i) In March 2018, Zambia fined Canadian company First Quantum Minerals US$7.9 billion for unpaid import duties.

(ii) In 2017, Tanzania handed the UK-registered Acacia Mining Plc a tax bill for US$190 billion. Based on the current revenue of the company, it is estimated this will take two centuries to pay.

(iii) In March 2018, The Democratic Republic of Congo ("DRC") revised its Mining Code to increase royalty rates on most minerals and introduced a 10 per cent royalty on minerals which are "strategic substances".

(b) Minimum state shareholding rights or "indigenous" shareholding rights

(i) In July 2017, Tanzania enacted amendments to its 2010 Mining Act, which included a minimum 16 per cent non-dilutable free-carried government interest in any mining company operating under a mining licence.

(ii) In 2017, Kenya's Mining (State Participation) Regulations included a free-carried 10 per cent state equity interest in any mining right granted after 27 May 2016.

(iii) In January 2018, new regulations under the Tanzania Mining Act introduced a requirement to have at least five per cent ownership by an "indigenous Tanzanian company" to be eligible for the grant of new mining licences.

(iv) In 2017, South Africa introduced similar requirements for minimum Black investor shareholdings in its revised Mining Charter (published in 2017, now subject to an appeal in the South African courts, and with a revised draft published in 2018).

(c) Minimum requirements for local sourcing of goods, labour and services, or bans on the export of unprocessed minerals (requiring processing to take place domestically)

(i) An export ban on unprocessed minerals was a key component of Tanzania's 2017 changes to its Mining Act.

3.3 The reasons for such measures are mixed. Some are driven by political objectives, such as in South Africa where measures are directly connected to the post-apartheid promotion of black economic empowerment. Others occur where governments implement measures in a bid to raise local revenue and cure social unrest. And, others seem to correspond solely to an increase in commodity prices globally.

4. the impact of resource NATIONALISM

4.1 The effects of resource nationalism can be significant.

4.2 It is therefore important that investors are informed of what options they have to protect themselves and mitigate any negative consequences.

Ashurst's experience of advising investors in relation to disputes with host states includes advising: · two African subsidiaries of an international mining company following enactment of tax and royalty changes under tax stabilisation provisions governed by the laws of a Southern African state and relevant rules of international law; · an international oil company in relation to recovery of tax and the enforceability of tax exemptions in a dispute with an East African state; and · an international mining company in relation to a dispute arising from the withdrawal of tax exemptions in a West African country. Guantao’s experience of advising investors in relation to disputes with China as the host state includes advising: · a Netherland energy group in relation to an investment dispute with China as the host state (ICSID arbitration); and · a European company in relation to an investment dispute with China as the host state (SCC rules). |

5. INVESTOR OPTIONS

5.1 Various options are available to mitigate exposure to the effects of resource nationalism. It will depend on the particular circumstances as to which tactics are employed.

5.2 Treaty protection: one of the more frequently invoked ways to protect investments is by ensuring that there is an investment treaty in place between the state in which one is investing (the host state) and the home state of the investor.

There are essentially two types of such treaties, Bilateral Investment Treaties ("BITs") and Multi-lateral investment treaties ("MITs"). These treaties offer varied protections for foreign investors, but usually include protection from expropriation without compensation and also an entitlement to fair and equitable treatment by the host state. If there is no treaty between the host state and the investor's home state, it may be possible to route the investment through a state that does have a treaty in place with the host state. Care must be taken with this option, however, as structuring an investment in order to protect against the effects of an existing, or foreseeable, dispute may not attract protection under the treaty.

5.3 Host state investment laws. The laws of the host state may provide protection for foreign investors, although reliance on such laws may be less productive in circumstances where it is the host state that has implemented measures giving rise to a complaint.

5.4 Investment contracts. An investor might conclude a contract directly with the host state or an entity owned by the host state in the form of a licence or concession. It may be possible to negotiate clauses which protect the investor, for example if there is a change in law or regulation which adversely affects the investor's interests (known as a "stabilisation clause"). An investor may also be advised to make reference in the contract to any relevant BITs and include confirmation that the investor is an "investor" and the contract is an "investment" for the purposes of that BIT. Such contracts are also usually subject to international arbitration as the method of dispute resolution.

5.5 Political risk insurance. In certain circumstances investors can insure against risks such as changes in law or regulation. Insurance providers often look to see if there is existing investment treaty protection which, ideally, might include a subrogation clause allowing the insurer to step into the shoes of the investor for the conduct of any dispute with the host state.

5.6 Political lobbying or strategic litigation. This is another option available to investors after any event. Examples of this strategy being employed include, the ongoing legal challenges to the 2017 Mining Charter in South Africa and China's Zijin Mining Group's preparation to sue the DRC, along with Switzerland's Glencore, over revisions to the DRC's Mining Code published in March 2018.

5.7 Enforcement. Fundamental to the effectiveness of most of the protections listed above is the enforcement of an investor's rights should the host state breach its obligations under the relevant treaty or contract.

5.8 Most treaties provide for disputes to be resolved by way of international arbitration, often in accordance with the rules of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes ("ICSID"). It is therefore important for investors to be knowledgeable as to their rights and also the process of arbitration. Arbitration is preferable to having disputes heard in domestic courts, where judges may favour the host state. An international arbitration award is also more readily enforceable globally, than a domestic court judgment. This is discussed further below.

6. PROTECTIONS for chinese investors

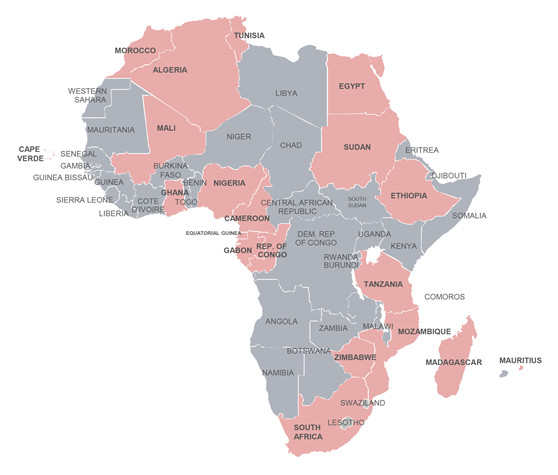

6.1 China has entered into BITs with 35 African states, of which 20 are currently in force.

Figure 1: BITs in force between China and African countries.

1.1 Some older treaties entered into before 2000 have more limited investment protections. Many do not contain "national treatment" clauses, which protect investors against states discriminating in favour of their national companies at the expense of the investor. For example, the BITs concluded with Ghana (1989), Egypt (1994), Mauritius (1996), Zimbabwe (1996), Algeria (1996), South Africa (1997), Ethiopia (1998) and Cape Verde (1998). The outlier is Morocco (1995) which contains a national treatment clause as well as a most favoured nation clause.

1.2 Some treaties also have restrictions on investors initiating arbitration proceedings against states by limiting the scope of arbitration to the amount of compensation for expropriation only (rather than for claims for breach of other treaty provisions – such as the entitlement to fair and equitable treatment). However, a number of recent arbitral decisions have broadly interpreted such clauses, finding that the question of whether or not an expropriation had occurred was also arbitrable and not just an issue concerning the amount of compensation. See Tza Yap Shum –v- Republic of Peru (under the China-Peru BIT) and Sanum Investments Ltd –v- Lao People's Democratic Republic (under the China-Laos BIT).

1.3 More recent treaties tend to allow a broader range of disputes to be referred to arbitration. For example, BITs signed post-2000 such as those with Nigeria (2001), Botswana (2000), Republic of the Congo (2000), Kenya (2001), Cote D'Ivoire (2002), Djibouti (2003), Uganda (2004), Benin (2004) and Madagascar (2005) provide that investors will be treated no less favourably than investors from the home state. Those treaties also do not restrict the types of disputes which may be referred to an arbitral tribunal.

1.4 To date, there have been only five investment treaty arbitrations involving Chinese investors relying on Chinese BITs, the first being initiated in 2007. None of these arbitrations involved African host states. However, the case of Beijing Shougang and others –v-. Mongolia, under which three Chinese companies with investments in a Mongolian iron mine are claiming compensation for expropriation following the Mongolian government's revocation of their mining licence, illustrates the type of claims which Chinese investors may have against host states.

1.5 International arbitration, and especially investment treaty arbitration, is not as widely participated in by Chinese investors as it is by investors from other parts of the world such as European states or the United States of America.

1.6 Investment treaty arbitration can differ in some respects from the ways in which Chinese investors may be used to approaching dispute resolution. A few points of difference are noted below:

(a) Investment treaty arbitration is different from concepts such as mediation-arbitration (or conciliation arbitration) which is commonly practised in China. In investment treaty arbitration, the tribunal will not act as a mediator nor will it actively encourage the parties to reach a settlement in the same way as a tribunal might in mediation arbitration. The Tribunal's task is more akin to a judge in a court – it will listen to the case of each party and then reach a decision, known as an arbitral award which will be final and binding on the parties.

(b) The process is also likely to be more adversarial in nature than many Chinese investors might be accustomed to. It is not commonplace for parties to adopt a conciliatory approach to arbitration. Parties to international arbitration seek to put forward their strongest arguable position, and avoid making any statements which might be interpreted as admissions of fault.

(c) Contemporaneous evidence is of great importance in international arbitration and the Tribunal will normally give significant weight to contemporaneous documents that evidence relevant facts. It is important therefore for Chinese investors who may find themselves in arbitration proceedings to keep accurate records of their investments (such as costs incurred and profit projections) and related issues. It is also important to note that the Tribunal will likely have the power to request that certain documents be produced by the parties if they are relevant and even if the parties have not previously volunteered them.

(d) It is important to make sure that any potential witnesses are properly familiarised with the arbitration process and are supported (as far as possible) by the party they are giving evidence for. Reluctance to admit mistakes or accept responsibility may mean that witnesses appear evasive and their testimony is given correspondingly less weight by a Tribunal.

2. the future

2.1 International arbitration is becoming more prevalent as a means of resolving disputes involving Chinese parties. This is only likely to increase as China advances its Belt and Road initiative across a wide array of overseas projects. The combination of increased Chinese investment in Africa, particularly in its minerals and resources, and the trend in a number of African countries to implement protectionist measures in respect of their resources, means that investor-state disputes between Chinese parties and African states are likely to increase in the future.

2.2 We are also likely to see the greater influence of Chinese approaches to dispute resolution on international investment disputes. In particular, the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission ("CIETAC") published International Investment Arbitration Rules in September 2017, with the aim of administering investment disputes involving Chinese parties. Although these rules reflect many of the prevailing trends in investment arbitration rule-making, they also incorporate Chinese characteristics – one provision governs the combination of conciliation with arbitration proceedings with a view to achieving settlement. To be used, CIETAC International Investment Arbitration Rules need to be included in BITs or a specific investment agreement as a dispute resolution mechanism, and this will largely depend on the negotiating power of China or the Chinese investor.

2.3 Chinese parties should keep up to date with these developments, and ensure generally that they are familiar with the options available to mitigate investment risk so as to place them in the best position to successfully develop their interests in Africa.