The primary characteristics of a loan include: (i) it is a debt, not a stock; (ii) the pricing instrument of a loan is the interest rate; (iii) a note is usually the evidence of indebtedness; (iv) the most important information regarding a loan are the principal amount, interest rate, and date of repayment.

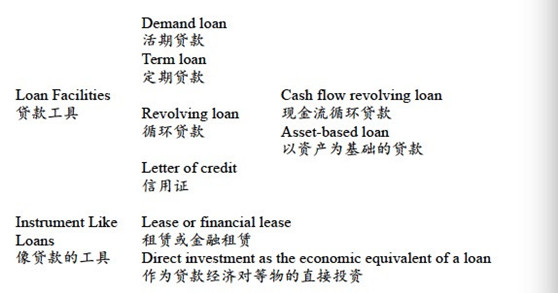

Traditionally, there are four loan facilities: demand loans, term loans, revolving loans, and letters of credit (“L/C”).

A demand loan is a loan without maturity date, it would be due whenever the lender demands. It is often seen in the lower end of the market, rarely seen in larger loans. A term loan is a loan for a specific amount that the borrower borrows on day one and then pays back according to a predetermined schedule. A revolving loan is a loan under a revolving facility which is a credit facility that can be borrowed, repaid and reborrowed at any time prior to maturity, at the borrower’s discretion. Any amounts outstanding on the maturity date must be repaid, in full, on that day. Moreover, a revolving facility can also often be used for the issuance of letters of credit as sublimit of the revolving facility. Two revolving facilities are popular, cash flow revolving loans and asset-based loans. A cash flow revolving loan is a revolving facility that provides the borrower with a line of credit up to a fixed amount. An asset-based loan is a revolving facility where the total amount that can be borrowed fluctuates based upon the value of certain assets of the borrower at a given time. Unlike a cash flow revolver, an asset-based loan is based on the value of certain categories of the borrower’s assets as of a given time, and limits the line of credit to the lesser of a fixed amount and a percentage of the value of a certain set of assets (primarily accounts receivable and inventory). Such limitation is often referred to as a borrowing base.

A letter of credit can be either a separate facility or a sublimit of a revolving credit facility. If the loan facility is available for letters of credit, it must be determined whether letters of credit are a separate facility or are a sublimit of the revolving credit facility. Most revolving facilities provide that a portion of such facility may be used in the form of letters of credit. A letter of credit, or L/C, essentially acts as a guarantee by one of the lenders (i.e. the issuing bank) under the revolving facility that kicks in if the borrower (the “account party”) does not meet an obligation to a third party (the “beneficiary”). Commercial letters of credit and standby letters of credit are two main types of letters of credit.

Instruments Like Loans

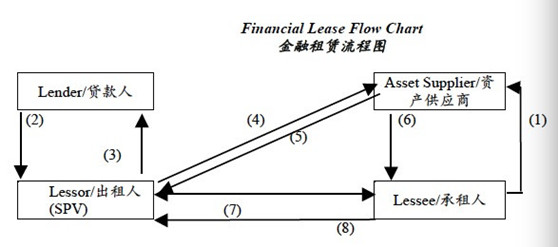

Notwithstanding, traditional loans do not satisfy the modern world any more. One instrument embedding a loan that has come into the financial world is a lease, or financial lease. UNIDROIT Model Law On Leasing defines financial lease in this way, “Financial lease means a lease, with or without an option to purchase all or part of the asset, that includes the following characteristics: (a) the lessee specifies the asset and selects the supplier; (b) the lessor acquires the asset in connection with a lease and the supplier has knowledge of that fact; and (c) the rentals or other funds payable under the lease take into account or do not take into account the amortization of the whole or a substantial part of the investment of the lessor.”

(1) specifies the asset and select the supplier;

(2) makes a loan;

(3) issues a note;

(4) procure the asset;

(5) transfers the title of the asset;

(6) deliver the asset;

(7) signs a lease;

(8) pay the funds;

In the real world, a financial institution qualified to make a commercial lending often establishes a special purpose vehicle (“SPV”) to be the lessor to make the lease, and the jurisdictions of incorporation of SPVs are almost some specified countries or regions for tax consideration. This is kicking off a financial lease but not mentioned in UNIDROIT Model Law On Leasing.

The above “4+1” instruments are either just true loans, i.e. demand loan, term loan, revolving loan, and letter of credit, or an combined instrument involving a loan. All of them fall within the federal banking law regarding loan. Is there anything else can be used by banks to fund their clients? The short answer is yes. Another instrument can be found in the modern loan world, being employed by banks to fund clients.

In the U.S., banks can be organized under state or federal law. Each state has its own version of a bank-chartering statute. Therefore, there is no “recommended form” of bank chartering law; they vary widely from state to state. For simplicity, the 50 states are ignored and just federal law is discussed here.

If a bank is organized under federal law (and most large US banks are), it is chartered by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (“OCC”) under the National Bank Act (12 U.S.C. §1, et seq). The National Bank Act was passed in 1864 – just after the Civil War – as one of many efforts to reunite the industrializing economies in the northern states and the agrarian economies in the southern states. The language of this 1864 statute is not modern. For example, the statute uses the word “association” where, today, we would say “bank”.

The powers of a national association (i.e., a national bank) are set forth in 12 U.S.C. §24. Its power to make loans is found in 12 U.S.C. §24 (seventh), which says a national bank shall have the power:

Seventh. To exercise by its board of directors or duly authorized officers or agents, subject to law, all such incidental powers as shall be necessary to carry on the business of banking; by discounting and negotiating promissory notes, drafts, bills of exchange, and other evidences of debt; by receiving deposits; by buying and selling exchange, coin, and bullion; by loaning money on personal security; and by obtaining, issuing, and circulating notes according to the provisions of title 62 of the Revised Statutes. The business of dealing in securities and stock by the association shall be limited to purchasing and selling such securities and stock without recourse, solely upon the order, and for the account of, customers, and in no case for its own account, and the association shall not underwrite any issue of securities or stock.

[emphasis added]

The power to make loans is found in these words: “by loaning money on personal security.” That’s all there is. Over the years, these words have been interpreted to allow all of the lending that federally chartered banks do today.

One way to confirm this in “modern law” is to look for regulatory pronouncements on the subject. Creative people are constantly coming up with new ideas for commercial lending and the regulators are called upon to rule on whether it is legal for banks to engage in such transactions. For example, banks are considering creative ways to finance to renewable energy projects. As a matter of public policy, regulators should be inclined to help, because renewable energy is a welcome alternative to fossil fuels. There is a 2013 OCC letter discussing – and approving – a bank’s power to invest directly in a company that will own a solar power facility. In this letter, the OCC rules that although the transaction is structured as a bank owning a power facility (which is not permitted), the substance of the transaction is the same as if the bank had lent money to the project sponsors, and so the OCC permits it as the economic equivalent of a loan.

While this expansive ruling (i.e., expansive because the OCC ignores the plain words on the transaction documents and focuses on the economic substance of the transaction) is interesting on its own, we call it to your attention because of the last paragraph on page 2:

A national bank may engage in activities that are part of, or incidental to, the business of banking. Twelve U.S.C. § 24(Seventh) provides national banks with broad authority to make loans or other extensions credit. Both the OCC and the courts have held that permissible loan equivalent transactions can take different and non-traditional forms in order to accommodate the demands of the market; the economic substance of the transaction, rather than its form, guides the analysis of whether the transaction is a permissible lending activity. Here, the alternative form of the transaction does not change the fundamental substance of the Bank’s role as a provider of credit.

[emphasis added]